Balancing Abstraction and Flexibility in Design Components

The Delicate Dance: Mastering Abstraction and Flexibility in Component Design

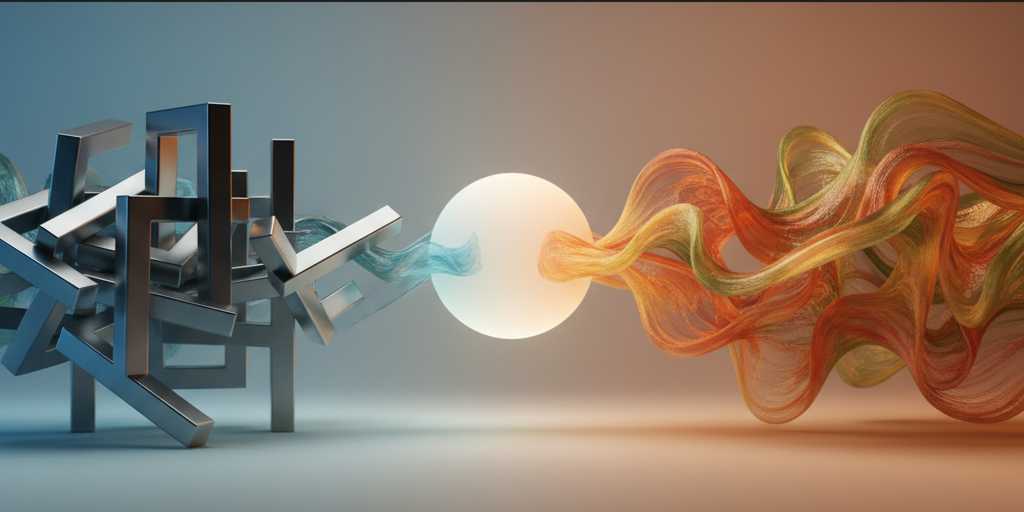

In the modern landscape of software development, particularly within the paradigm of component-based architectures for front-end and back-end systems, a fundamental tension lies at the heart of every design decision. It is the perpetual tug-of-war between two powerful, often opposing, forces: Abstraction and Flexibility. To craft components that are both robust and enduring, a developer must become a masterful tightrope walker, balancing the clean, black-box simplicity of abstraction with the raw, adaptive power of flexibility. Leaning too far in either direction leads to systems that are either too rigid and “magical” or too complex and inconsistent. This article delves into the nature of this balance, exploring the perils of imbalance and outlining strategies for achieving a harmonious synthesis.

Part 1: The Allure and Peril of Abstraction

Abstraction is the process of hiding complex implementation details behind a simplified interface. It is the cornerstone of software engineering, enabling developers to build upon the work of others without needing to understand the intricate inner workings.

The Virtues of Abstraction:

- Developer Experience (DX): A well-abstracted component is a joy to use. It offers a clean, declarative API. Think of a sophisticated

DataTablecomponent. A consumer simply passes incolumnsanddataprops, and a fully functional table with sorting, pagination, and filtering materializes. The developer doesn’t need to concern themselves with the event handlers for column headers, the logic for slicing data into pages, or the state management for filter criteria. - Consistency and Standardization: Abstraction enforces uniformity. By providing a single, vetted way to solve a common problem (e.g., a

PrimaryButtoncomponent), it ensures that the application’s look, feel, and behavior remain consistent across different teams and features. - Reduced Cognitive Load: By encapsulating complexity, abstraction allows developers to focus on the business logic of their specific feature rather than the plumbing of UI or service interactions. It elevates the level of discourse from “how do I make this click handler work?” to “what should happen when the user confirms this action?”

- Maintainability and Bug Reduction: When logic is centralized within an abstracted component, a bug fix or an improvement needs to be made in only one place. This is far superior to hunting down the same flawed logic duplicated across a dozen different files.

The Pitfalls of Over-Abstraction (The “Black Box” Problem):

However, when abstraction is taken too far, it transforms from a helpful tool into a crippling constraint.

- The “Prop Explosion”: In an attempt to anticipate every possible use case, a component’s API can become a bloated list of props. A simple

Buttonmight end up withvariant,size,color,isLoading,disabled,leftIcon,rightIcon,onClick,onHover, and a dozen more. The component becomes a configuration nightmare, and its simplicity is lost. - Leaky Abstractions: Coined by Joel Spolsky, this law states, “All non-trivial abstractions, to some degree, are leaky.” This means the underlying complexity inevitably seeps through. What happens when a designer requests a pagination layout that the

DataTablecomponent doesn’t support? The abstraction “leaks,” forcing the developer to use CSS hacks, fork the component, or abandon it altogether, defeating its purpose. - Inflexibility and “One-Size-Fits-None”: An overly abstracted component can become a golden cage. It works perfectly for the 80% of cases it was designed for but becomes a massive obstacle for the 20% that require a slight deviation. The effort required to extend or modify the component often exceeds the effort of building a custom solution from scratch.

- Obscured Complexity: When something goes wrong inside a deeply abstracted component, debugging can be a herculean task. The developer is forced to delve into layers of code they never intended to touch, navigating a maze of internal state and side effects they are unfamiliar with.

Part 2: The Power and Chaos of Flexibility

Flexibility, in this context, refers to a component’s capacity to be adapted, composed, and extended to suit a wide variety of needs, including those not originally envisioned by its author.

The Strengths of Flexibility:

- Adaptability to Change: Requirements are volatile. A flexible component system can gracefully handle new design trends, unique business logic, and unexpected use cases without requiring a complete rewrite.

- Empowerment and Control: Flexible components empower developers. Instead of being limited by a pre-defined API, they have the primitives to compose complex behaviors from simple, predictable parts. This is the philosophy behind libraries like React itself, which provides fundamental hooks (

useState,useEffect) as building blocks. - Future-Proofing: It is impossible to predict all future requirements. A flexible, composable architecture is inherently more resilient to the test of time than a rigid, monolithic one. It acknowledges the uncertainty of software development.

The Dangers of Excessive Flexibility (The “Legacy Quagmire”):

Without guardrails, flexibility descends into chaos.

- Inconsistency: If every developer is empowered to build a table in their own way, the application will soon have ten different table implementations with slightly different behaviors, accessibility features, and performance characteristics.

- Increased Cognitive Load: While good abstraction reduces load, bad flexibility increases it. Developers can no longer make assumptions about how a “table” works; they must read the specific implementation for each one they encounter.

- Boilerplate and Repetition: Highly flexible, low-level primitives often require a lot of boilerplate code to achieve common tasks. While this offers ultimate control, it sacrifices developer efficiency and opens the door for subtle errors and inconsistencies in the boilerplate itself.

- Weak Foundations: A system that is too flexible provides no opinionated guidance. This can lead to poorly thought-out implementations and architectural drift, where the codebase gradually becomes a collection of disjointed solutions rather than a cohesive system.

Part 3: Strategies for Achieving the Equilibrium

The goal is not to choose between abstraction and flexibility, but to find their symbiotic sweet spot. Here are key strategies to achieve this balance.

1. Embrace Composition over Configuration (“Slot” Patterns): This is arguably the most powerful technique. Instead of configuring a component via a long list of props (configuration), you allow parts of it to be replaced or extended by passing in other components (composition).

- Example: A

Cardcomponent should not haveheaderText,headerImage,footerActionsprops. Instead, it should provide “slots.”

This approach offers a high-level abstraction (<Card> <Card.Header> <Avatar user={user} /> <h3>Custom Title</h3> </Card.Header> <Card.Body> <p>Any content can go here, including other components.</p> <Chart data={data} /> </Card.Body> <Card.Footer> <Button variant="primary">Custom Action</Button> <Link to="/details">Learn More</Link> </Card.Footer> </Card>Cardwith its structure and styling) while granting maximum flexibility over its content.

2. Stratified Design: Build a Layer Cake of Abstraction Don’t build a single, monolithic component. Build a foundation of low-level, highly flexible primitives and then compose them into higher-level, opinionated abstractions.

- Level 1 (Primitives):

Box,Text,Input,Icon. These are highly flexible, unstyled (or minimally styled) building blocks. They have very few opinions. - Level 2 (Composed Components):

FormField(composesLabel,Input,ErrorText),Button(composesBox,Text,Icon). These add sensible defaults and specific behaviors. - Level 3 (Domain-Specific Components):

ProductCard,SearchFilters. These are highly abstracted components tailored to specific business contexts.

This structure allows developers to use the high-level components for 80% of the work and “drop down” to the primitives when they need to build something unique, without leaving the design system.

3. Sensible, Overridable Defaults A component should work perfectly out-of-the-box with zero configuration. However, its appearance and behavior should be easily overridable when necessary.

- Use props to control the primary variations (

variant="primary"). - Expose a

classNameprop to allow for custom CSS, but scope it properly to avoid breaking the component’s internal layout. - Consider a

stylesAPI or a CSS-in-JScssprop that allows targeting internal elements in a controlled manner, which is safer than a rawclassName.

4. The Principle of Least Power Choose the most restrictive, simplest abstraction that can do the job. Only add complexity when a clear, concrete need arises. Resist the urge to build for hypothetical future requirements. Start with a inflexible but perfectly suited component, and only generalize it when a second, similar use case emerges.

5. Explicit over Implicit (“Magic” is the enemy) A component’s behavior should be predictable. Avoid “magic” where props are inferred from context in ways that are not obvious. It’s better to have a slightly more verbose API that is explicit and understandable than a concise but mysterious one. Good documentation is the final, crucial layer that makes a balanced component system usable.

Conclusion: The Art of the Possible

The balance between abstraction and flexibility is not a static line but a dynamic equilibrium that must be constantly assessed and recalibrated. It is a core aspect of the art of software design. A successful component library or system is one that feels like a guided tour, not a prison. It provides paved paths for the common journeys, ensuring speed, safety, and consistency. Yet, it also leaves the maps available and the tools accessible, empowering explorers to venture off the path and create new, unforeseen solutions when the business demands it.

By prioritizing composition, building in stratified layers, and valuing sensible defaults, we can craft components that are not just tools, but partners in development. They abstract away the repetitive and the trivial, freeing up human creativity to tackle the truly unique and complex problems that define a great product. In the end, mastering this balance is what separates a collection of code from a truly elegant and enduring design system.