Speed vs. Sustainability: The Eternal Dilemma in Software Architecture

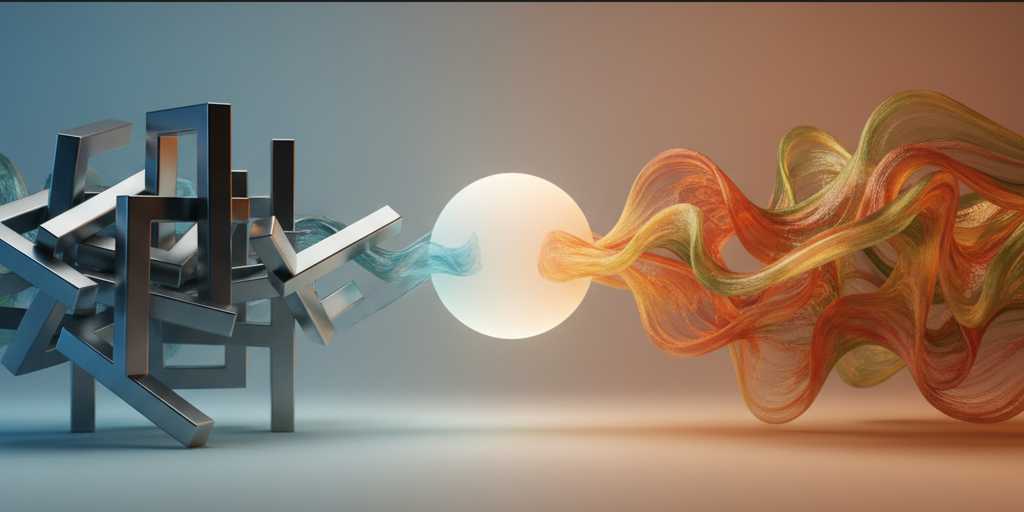

Software architecture is one of the most complex challenges in modern application development. Every development team faces this difficult choice: should we prioritize speed of delivery to meet immediate market needs, or invest in a sustainable architecture that will ensure the maintainability and scalability of the system in the long term? This constant tension between the short term and the long term deserves a thorough analysis.

Understanding the Two Extremes of the Spectrum

The Trap of Over-Engineering

Over-engineering occurs when a team designs a solution that is far more complex than necessary. This approach is like using a sledgehammer to crack a nut. The symptoms are recognizable:

- Excessive Abstraction: Creating superfluous layers of abstraction that weigh down the codebase without tangible added value.

- Premature Generalization: Developing “just in case” features rather than responding to concrete needs.

- Inappropriate Technologies: Introducing complex frameworks or tools to solve simple problems.

- Disproportionate Architectural Patterns: Rigidly applying patterns like CQRS, Event Sourcing, or Microservices in contexts where they are not justified.

The consequences of over-engineering are severe: slowed development speed, a steeper learning curve for new developers, and difficulty pivoting quickly when needs change.

The Danger of “Quick and Dirty”

At the other end of the spectrum, the “quick and dirty” methodology promises rapid delivery at the expense of technical quality. This approach seems appealing in a context of aggressive time-to-market, but it generates exponential technical debt:

- Absence of automated tests, making refactoring perilous.

- Code duplication, leading to inconsistencies and multiple fixes.

- Non-existent or outdated documentation.

- Strong coupling between the different modules of the application.

The accumulated technical debt eventually slows the team down considerably, sometimes to the point of making the application impossible to maintain or evolve.

Strategies for Navigating Between These Two Pitfalls

Adopting Evolutionary Architecture

Evolutionary architecture is based on a simple principle: build only what you need today, but anticipate likely future changes. This approach requires:

Determining Flexibility Points: Identify areas of the system that are likely to change frequently and isolate them behind stable interfaces. For example, in an e-commerce application, the payment system is highly likely to evolve (adding new payment methods, regulatory changes). Isolating this functionality behind a well-defined interface limits the impact of future changes.

Practicing YAGNI (You Ain’t Gonna Need It) with discernment: This agile principle recommends developing only the features for which there is an immediate need. However, it should not be applied dogmatically. The key is to distinguish what is easy to add later from what will be very costly to refactor.

Implementing Differential Quality

Rather than aiming for uniform quality across the entire codebase, adopt a differentiated approach based on the criticality of each component:

Critical Code: Central, complex components that are unlikely to change deserve special attention (comprehensive tests, detailed documentation, rigorous code reviews).

Non-Critical Code: Peripheral or simple features can follow less demanding standards, provided their isolation allows them to be easily refactored if necessary.

Establishing Effective Feedback Loops

The ability to quickly detect architectural problems is crucial for adjusting the balance between speed and sustainability:

Regular Architecture Reviews: Organize dedicated sessions to examine architectural decisions, with a particular focus on the trade-offs made.

Objective Measures of Technical Debt: Use tools like SonarQube to quantify technical debt and track its evolution over time.

Early User Feedback: Regularly integrate user feedback to validate that technical choices are serving business needs.

The Crucial Role of Context in Architectural Decisions

Factors Determining the Required Level of Sustainability

Not all applications have the same architectural requirements. Several factors should influence your decisions:

Anticipated Lifespan: An application intended to be used for years justifies more architectural investment than a prototype or a minimum viable product (MVP).

Team Size and Experience: An experienced and stable team can handle a more complex architecture than a newly formed team or one with junior members.

Business Criticality: Applications supporting critical business processes (health systems, financial systems) require a more rigorous approach than internal or single-use applications.

Expected Scalability: The anticipated volume of data and traffic should guide architectural choices, particularly regarding databases and caching strategies.

Adapting the Approach to the Product Lifecycle

The phase your product is in should influence your architectural approach:

Discovery Phase (MVP, proof of concept): Prioritize speed and flexibility. Use frameworks that allow for rapid prototyping and be prepared to throw away code.

Growth Phase: Strengthen the foundations, introduce more structure, and start paying down the technical debt accumulated during the previous phase.

Maturity Phase: Optimize for performance and maintainability. This is the time to invest in deep refactoring if necessary.

Practical Techniques for Balancing Speed and Sustainability

The Concept of “Just-in-Time” Architecture

Inspired by lean manufacturing principles, “just-in-time” architecture consists of:

Deferring Irreversible Decisions: Make easily changeable decisions immediately, but postpone hard-to-reverse decisions until you have enough information.

Implementing Simple Solutions First: Start with the simplest solution that could possibly work, then iterate based on feedback and emerging needs.

Planning for Extension Points: Without immediately implementing all possible features, design the system to easily add extensions later.

Contracts and Interfaces as Stabilization Tools

The judicious use of interfaces helps to reconcile stability and flexibility:

Define stable interfaces between major modules, allowing the implementation of each module to evolve independently.

Use semantic versioning for internal and external APIs, allowing for evolution without breaking existing clients.

Document implicit contracts between different parts of the system, especially expectations regarding performance and behavior.

Concrete Case Studies

Success Through Balance

Consider the example of a startup that successfully found the right balance. Their initial product was an MVP developed in three months with a simple but well-isolated architecture. Critical business components (payment management, price calculation) were well-structured and tested, while less critical features (admin interface, reporting) followed lighter standards.

As the company grew, the team gradually strengthened the architecture without having to rewrite everything. Well-defined interfaces allowed them to replace initial simplistic implementations with more robust solutions, with limited impact on the rest of the system.

Failure Through Excessive Complexity

Conversely, another company succumbed to over-engineering by adopting a microservices architecture for an application that didn’t need it. With only three developers and a limited functional scope, the operational complexity (service orchestration, data consistency management) absorbed 60% of the development time, significantly slowing down the delivery of business features.

Conclusion: Towards a Dynamic Balance

The balance between speed and sustainability is not a static state to be achieved once and for all, but a dynamic adjustment that must evolve with the project’s context. The key lies in a constant awareness of trade-offs and the ability to regularly adjust the approach based on feedback and evolving needs.

The best teams are not those that always avoid technical debt or build architectural cathedrals, but those that know when and how to invest in quality, constantly aligning technical decisions with business objectives.

Architectural wisdom ultimately consists in recognizing that no decision is final, but that some decisions are harder to reverse than others. By focusing your efforts on these potential points of no return, you will maximize the impact of your architectural investment while preserving the agility needed to respond to unforeseen events and opportunities.